“The sound and general mechanism of modern instruments,” says Mr. Burge, “are certainly superior to those of Father Smith’s, but for sweetness of tone I have never met in any part of Europe with pipes that have equalled his” Walter Thornbury, 1878

1644 was a fateful year for church organs in London, as in other parts of the country. Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth abhorred over-indulgence, and on 4 January an ordinance from Parliament sounded the death-knell for the heavenly pipes.

Symbolically, like men hanged, drawn and quartered for treason, churches were to have their organs removed. To Cromwell and co, these instruments had come to symbolise a superstition and vanity that had to be expunged from the house of the Lord.

Very few survived, and among those destroyed was one at Temple Church, off Fleet Street. Although the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 mean that churches could once again be filled with the joys of piped music, indigenous organ-building skills appear to have been lost. Of course many entire places of worship would also need rebuilding following the Great Fire in 1666.

Eighteenth century musicologist Dr Burney reports that ‘it was thought expedient to invite foreign builders of known abilities to settle among us; and the premiums offered on this occasion brought over the two celebrated workmen Smith and Harris.’

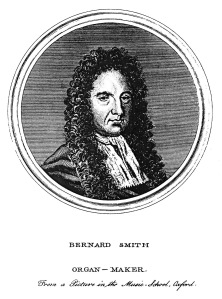

Bernard Schmidt (ca 1630-1708), a German better known in England as ‘Father’ Smith, was ‘renowned for his care in choosing wood without knot or flaw, and for throwing aside every metal or wooden pipe that was not perfect and sound. His stops were also allowed by all to be singularly equal and sweet in tone.’ (Walter Thornbury: ‘Old And New London,’ volume one.) With first mover advantage, Smith rapidly signed up several churches around the City of London and became the king’s organ maker.

Soon, though, he found himself losing business to a modernising young upstart, Renatus Harris (ca 1652-1724), the son of an English organ builder, born in France during Cromwell’s rule. Each swiftly built up a loyal following of supporters and detractors throughout the City and beyond.

Smith was first to approach the Temple Church, one of London’s most prestigious places of worship, and offer to install a new organ on a trial basis. In February 1683 the Temple Master and Benchers asked him to build one – but in neighbouring premises owned by the Inns of Court.

The German was convinced he was alone in tendering, and was reportedly vexed when he learned that bitter rival Harris had successfully argued to be allowed to compete.

In a neat piece of one-upmanship, Smith managed to convince the church Benchers that his instrument should be installed within the church itself, rather than in an adjoining lawyers’ hall.

When Harris was informed, he demanded and was given parity. As a result, Smith’s grand pipe organ would be built on one side of the church, and Harris’s on the other.

If that sounds like a classic British compromise, the rivalry during the design and construction phase escalated into a musical arms race.

Both builders attempted to outdo each other in scale, numbers of pipes and knobs, new effects and the like. When Harris built in a vox humana or violin emission, he threw down the gauntlet at Smith to do likewise. It would almost ruin both financially.

With the two great organ builders pulling out all stops (quite literally), by early 1684 both wind-beasts were finished. The biggest instruments ever known in London faced each other across the church floor, and a date was set for the sound contest.

Anyone who attended a ‘clash’ between London’s reggae sound systems of the 1970s and 1980s would recognise the format.

In 1684 the two crews employed similar tactics to a Saxon or a Channel One sound system, too: they looked to sonic novelty and innovation, and even subterfuge, to win over their audience.

The night before the soundclash, Harris’s helpers were accused of slitting the bellows of the Smith organ, so that ‘when the time came for playing upon it no wind could be convaeyed into the windchest’ – the equivalent of nicking your opponent’s amp from his Transit van.

Just as a reggae soundsystem would recruit the best selectors, dub plates and singers available, Smith and Harris recruited the great and good of European music to play for them.

No less a figure than Henry Purcell was among the many to tinkle the ivories for Smith, while Harris borrowed the queen’s pet organist from France, Mr Lully.

The ‘battle of the organs,’ which went on for almost a year without a winner, caused a sensation in London and no little PR for the combatants.

Eventually it fell to the infamous Lord Chief Justice Jefferies to decide in favour of Father Smith. Finally, on 20 June 1688, the German was recompensed £1,000 (just under £90,000 today) for his most generous organ donation.

Having been substantially overhauled over the intervening years, what remained of Father Smith’s Temple organ was completely destroyed by incendiary bombing on the night of 10 May 1941.

The present instrument, built by Harrison and Harrison of Durham, was donated by Lord Glentannar and installed – without challenge – in 1954.

Part of Harris’s losing contraption wound up at St Andrew’s, Holborn, while some of the victorious pipes from that epic soundclash are still on display today in the vestry of the Temple Church.