I have met hundreds of people through family history research. Some are long lost cousins. Others are researching the same ancestors but have no blood relation. An example of the latter is Stan Rondeau. Visitors to the remarkable Christ Church in the old Huguenot heartland of Spitalfields may well have been met and gret by Stan, who provides ‘living history’ as a guide there.

To me, though, Stan is near-miss Huguenot kith and kin: his ancestor John Rondeau (1754-1802) was the second husband of Magdalene Levesque (1756-1840), whose first spouse was James Vernell (1755-1790); they are my five-times-great grandparents.

Stan and I have met to share our research several times. A few months back we were exploring the local history archives in Enfield, where we knew of other individuals from the Rondeau and Levesque families.

My seven-times-great uncle Peter (or Pierre) Levesque was ‘upwards of 50 years organist in this church’ according to the register of St Andrew’s in Enfield’s ancient market square. The words were next to his burial entry on 1 January 1823. He was 78 and lived on Chase Side. By coincidence I went to school opposite St Andrew’s and lived for a while on Chase Side – ancestral footprints and all that.

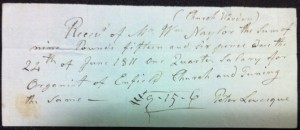

I hoped the church vestry minutes might provide further information on Peter’s half-century at the Enfield wicket and possibly suggest a new link between the Levesques and the Rondeaus. Well, we learned much, including that in 1811 the parish paid Peter £9 15s 6d per quarter to play and tune the organ – around £1,300 a year today.

Eleven years later ‘the situation of organist of this parish was declared vacant by the death of the late Mr Peter Levesque’ and a successor was to be chosen a few weeks later, each candidate to perform on the keyboard before a vote took place.

Remarkably, Stan’s ancestor James Rondeau was one of those whose ears would pass judgement.

There were four candidates: Miss Linton, Miss Leach, Mr Arnull and Mr Reeves. Tension rose when the vestry minutes for 6 March 1823 recorded that although, following the auditions, ‘a show of hands appeared and was declared in favour of Miss Leach’, sexism reared its head and a paper vote was demanded. Women were simply not supposed to take music-playing seriously in early C19th England.

‘Ooh,’ winced Stan as we browsed the columns of the voting record, ‘I do hope James did the right thing and voted for Miss Leach.’

Reassuringly, James Rondeau pulled out all the stops and his vote was indeed placed under the original winner, Miss Leach. An anachronistic family crisis was averted. I discovered afterwards that the first female member of England’s Cathedral Organists’ Association was only elected 180 years later.

Afterwards we strolled down to St Andrew’s church, where Stan inspected James Rondeau’s gravestone just that little bit more fondly. I surveyed the historic organ: tuned and played for 50 years by great uncle Peter, and then striking an early chord for Feminism, four years into the reign of Queen Victoria.