On 18 September 1625 London lawyer John Glanvill, on business in Plymouth, submitted to Charles I’s counsel a document he hoped would opt him out of his appointment as the crown’s observer on a huge, ill-starred naval attack against the Spanish at Cadiz.

The submission was archived as “Mr Glanvills reasons against his being imployed for a Secretary at Warre.” What follows is a transcript of his excuses and the background to them.

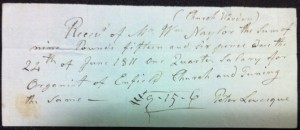

Excuse the fyrst. “He is a meere Lawyer, unqualified for h’imployment of a Secretary : his handwriting is so bad that hardly any but his Clarke canne reade itt, who shoulde not be acquainted with all things that may occurre in such a service.”

Well, he got this right: the handwriting is devilish bad. A pretty poor opening gambit nonetheless.

Excuse the secunde. “He hath a wife and six children, and his certaine meanes without his practise is not sufficient to maintain them.”

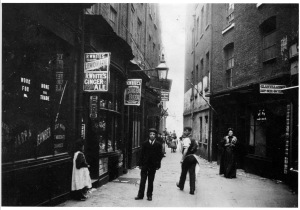

Tugging at the heartstrings now. The six children were William, Mary, Margaret, John, Francis and Walter – an unnamed child had died at birth six years earlier in March 1619 at Church Yard Alley, Fetter Lane, running adjacent and to the east of Chancery Lane. John and wife Winifred would have two further children: Elizabeth and Julius.

Excuse the thyrd. “He sitteth at 60li rent p annum for a house in Chancery Lane, not worth him in effect anie thing but for the commodiousness of his practise : however hee is to hold itt att that rate for 16 or 17 yeares yet to come.”

The precise whereabouts of his house on or near Chancery Lane are now unknown, but the King’s men would know it was just one of several properties in the Glanvill portfolio. His father, John the Elder, acquired numerous estates in the west country through the patronage of the Duke of Bedford. The Elder, a district judge who died in a fall from his horse on circuit in 1598, when son John was in his early teens, left him Kilworthy, a fine manor north of Tavistock, Devon, but John generously handed it to his older brother Francis. He had estates in Hampshire and Devon, and in later years he made his main domicile at Broad Hinton, Wiltshire, yet his letter to a Mrs Scott in Cocklebury in the same county in 1652 was dispatched from Serjeants Inn, Chancery Lane – he had been made serjeant in 1637. Incidentally, £60 rent is the equivalent of around six grand today. Very good luck in finding a pad in Holborn for that these days.

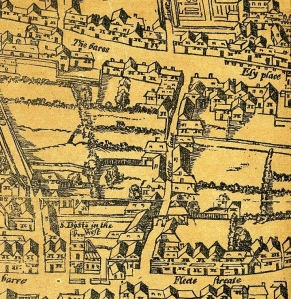

Circa 1560 map showing Fetter Lane (centre) and Chancery Lane (branching off to left). http://mapco.net/london.htm

Excuse the forth. “His wife and children are dispersed into four gen’rall counties, with severall frendes in Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, Gloucestershire and Devonshire, during his sicknes, and hee cannott in his straight and upon so short warninge, setle his affaires for such a journie.”

He has a point: the King was expecting him to disembark from Plymouth at the drop of a hat and be away on this mission for perhaps months. This is also the first documented mention of John’s ‘sicknes’, which recurred sporadically throughout his life – and eventually saw him off in 1661. Sadly the only clues to what the illness was simply describe how it laid him low for extended periods; tantalisingly, there is no discussion of symptoms.

The child-minding friends in Devonshire and Gloucestershire are easily imagined: he hailed from and worked in the former county and his wife Winifred was the daughter of Sir John Bourchier of Barnsley, Gloucestershire. The Herts and Beds connections require further investigation.

Excuse the fifth. “His goods and evidences and the evidences of divers of his clients with many breviattes and noates of instruccons concerninge their Causes, are in his Studdy att Lincolns Inne and house in Chancery Lane, which hee cannot well dispose nor distribut in a short tyme, nor can now safely repaire to the place[s] where they are.”

John was a commercial lawyer as well as MP and Recorder for the Plymouth corporation at the time. According to this submission his legal documents and case files were stored at Lincoln’s Inn, where he had trained and been called to the bar, and in his place next door on Chancery Lane. His argument is that sensitive manuscripts would be left as they are, unattended, in his absence.

At Lincoln’s Inn a splendid portrait of John (as well as one of his father) is still viewable by appointment.

Excuse the sixth. “Hee is witnesse to recordershipps and engaged in divers causes of importance, which affaires and businesses if he desert, much preiudice may thereby grow to very manie.”

This makes absolute sense. Apart from his paid counsel to corporations such as those of Plymouth, Okehampton, and Launceston, he was an extremely active MP and sat on numerous commons committees, particularly those related to his obsessive campaign against market monopolies and rotten boroughs.

Eleven speeches in the House and appointment to 16 conferences or committees in 1625 was a pipe down from his peak the year before of 84 speeches and 47 appointments, but this could be explained by his debilitating illness.

Excuse the seventhe. “His mother, an aged lady, who relies upon his Counsell and resort, will become herby much weakened and disconsolate.”

If in doubt, mention Mum. Glanvill’s redoutable twice-widowed mother, Lady Alice Godolphin (née Skerrett – she had remarried to Sir Francis Godolphin) was in her mid-70s at the time and died in 1632 aged 82. There is no evidence of frailty; her likeness in a memorial in St Eustachius, Tavistock, is a powerful one.

Excuse the eyghth. “His practise is now as good as most men in ye Kingdome of his tyme, hee having followed ye Studdy these 22 years and ye practise of ye lawe these 15 yeares, with as much Constancie and painefulness as anie man. And if hee should now bee putt into another course though but for a while, itt must needes deprive him of the fruictes of all his labours, for his Clients being by his absence once setled uppon others, he shal never be able to recontinue them again.”

It was always unlikely a whinge about lucrative clients switching allegiance might butter the King’s parsnips, even though some of them were illustrious and influential. What the information does confirm is that he entered Lincoln’s Inn in 1603, around the age of 17, and was called to the bar in 1609.

Excuse the nynthe. “His cominge to Plymouth att this tyme was only to attend ye service of his Recordershippe there, to assist the Maior and his brethren to entertaine his Majestie ; which service hee had p’formed accordingly.”

If begging wouldn’t work, perhaps a gentle reminder of what John had already done for His Maj would do the trick. And it was considerable. He, along with mayor of Plymouth, Nicholas Blake. and another merchant, Thomas Sherwell, were the members of parliament for Plymouth who received the King and his extensive household in September 1625, during which visit this document was written.

City records note the “Fees due to His Majesty’s servants from the said Mayor, for his homage to His Majesty passing through his said towne the fiveteene day of September, 1625.”

“To the Gentlemen Ushers dayly Wayters … £5

“To the Gent. Ushers of the Privy Chamber … £5

“To the S’jants. at Armes … £3

“To the Knight Harbinger … £3

“To the Knight Marshall … £1

“To the Gent. Ushers Quarter Wayters … £1

“To the Servers of the Chamber … £1

“To the Yeoman Ushers … £1

“To the Groomes and Pages … £1

“To the Footmen … £2

“To the fower Yeomen … £2

“To the Porters at the Gate … £1

“To the S’jant. Trumpetters … £1

“To the Trumpetters … £2

“To the Surveyor of the Wayes … £1

“To the Yeoman of the fielde … £10

“To the Coachmen … £10

“To the Yeoman Harbingers … £1

“To the Jester … £10.”

(Quoted in ‘History Of Plymouth’ by Llewellynn Jewitt; Plymouth 1873.)

Charles stayed for ten days. It was not simply the outlay required but the fact that religious turmoil and plague had recently hit Plymouth:

“The King cometh to Plymouth to despatch a fleet. He calls a Parliament and finds great discontent, the Presbyterian interest prevailing so as to ferment the people. A great plague in Plymouth, of which 1,600 people died — some say 2,000.”

The King’s agents also took the opportunity to press 500 men into naval service for his Raid on Cadiz under the command of Edward Lord Cecil. Who could do more for Charles than allow all this indulgence!

In the end the protests were to no avail. Sea-sick Glanvill was made secretary at war for the ill-conceived Cadiz raid and it was a cataclysmic flop.

He took his revenge in two very lawyerly ways.

Firstly he noted every moment of failure with sardonic enthusiasm in his official Journal, published by the Royal Historical Society 250 years later as ‘The Voyage to Cadiz In 1625.’

And secondly, in 1626, a year after the raid, Glanvill was one of the eight chief managers in the impeachment of the King’s favourite, the Duke of Buckingham, whose idea the raid was. Charles reacted by dissolving Parliament. And thus was erected another signpost along the road to Civil War.