Among the pleasures of tracing a distant cousin, Nigel Glanvill, a few years ago was the astonishing collection of family photos and letters in his possession. He kindly loaned me the entire pile and working through it I have felt like an amnesiac rediscovering my past, albeit of my Victorian ancestors.

The Glanvill family moved from Ashburton in Devon, via Exeter, to Clerkenwell, Middlesex, in the 1850s. They brought with them their trades – tailoring and bootmaking – as well as a determination to make more of their lives.

The patriarch was my three-times great-grandfather, Thomas Glanvill (1803-1867), a tailor and part-time Methodist zealot who according to one of the letters would ‘on Sundays mount a horse and be away preaching’ around rural Devon. He had been widowed in 1844, so the burden of looking after his younger children on the Sabbath fell to his increasingly resentful older sons.

His extended absences and the demands on his kids were balanced by excellent baking skills. According to his grandson Fred, his homemade steak and kidney puddings were easily the equal of ‘the fancy varieties at Simpsons or the Cheshire Cheese’ in the Big Smoke.

However, it may have been the invitation to start a Methodist ministry – as well as splendid pastries – in a new locality that attracted Thomas to a momentous move.

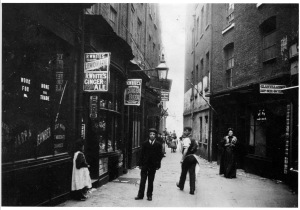

London, made more accessible by the railway reaching Exeter in 1844, also offered the prospect of a busier trade and social life for his grown-up children. Thomas took the plunge and moved his family to Clerkenwell, an area renowned for small workshops and cheap labour, just north of the old City wall.

It was from his new master tailoring premises at 11 Jerusalem Passage that Thomas wrote several times to his younger brother Richard, a haberdasher who had remained in Ashburton. Most of this correspondence – all randomly perforated by embers from the pipe of his brother as he read them – consists of religious ranting and Thomas’s battles to resist temptation while surrounded by sin.

One letter, however, dated 1861, speaks in wonderment of the kind of invention that would help his family flourish in the capital: one of the new ‘sewing machines’ that had been in mass production for just a few years.

‘Tom [his oldest son] hath bought a Sewing Machine for £8 10s [around £450 today],’ he marvelled. ‘He finds some difficulty with it at present. It is such a complicated piece of machinery that without a regular course of instruction it is not easily learnt.

‘I am sure it will require six months good practice to be anything like a master of it. However, it will go ahead and no mistake.

‘You can sew the seams in a pair of trousers, stitch the falls, put in the pockets, and make the linings in a quarter of an hour, after it is baisted.

‘There is silk and thread sold on purpose, but you cannot use double thread nor do anything but backstitch, but as fine or as coarse as you like.

‘My work has been very slack of late for three months and I believe every trade is complaining of the same. Notwithstanding I am very thankful indeed that it was so ordered in God’s providence for me to come to London.’

Thomas died in 1867 aged 64, but having mastered the new tailoring device, Glanvill & Sons survived for a further sixty years at 11 Jerusalem Passage.