It was once the stronghold of the most powerful foreign presence in the heart of medieval London, but the Steelyard (anciently Stiliards) is now buried and forgotten under Cannon Street Station. Its name is an Anglicisation of Stapelhof – possibly from the Latin ‘stabile emporium’, a place where prices were fixed for certain goods, or the Low German ‘stapel’, meaning warehouse or stage. And it is with merchants and guildsmen of Hamburg, Cologne and other northern European ports – the Hanseatic League – that the walled dock-cum-stronghold was associated for hundreds of years. The Hansa presence in the City of London was noted from the time of Ethelred in 967 and in 1260 Henry III announced:

“we have granted to these Merchants of Almain [Germany] who have a house in our City of London, which is commonly called Guilda Aula Theutonicorum [German Guildhall] that we will maintain them all and every one and preserve them through our whole Kingdom, in all their Liberties and free Customs, which they have used in our Times and in the Times of our Progenitors.”

In return for their privileges the influential foreign merchants maintained the City’s Bishopsgate and would summon a third of the men required to defend it when necessary. The King’s crane-balance for weighing the tonnage of goods arriving in London’s port was based here before moving to Cornhill. It must have been a familiar waterfront landmark for Londoners.

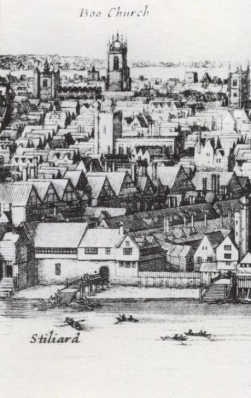

The Steelyard wharf and stairs detailed in Wenceslaus Hollar’s 1647 panorama. Cockneys NB: Bow Church in the background.

In 1598 John Stow described the stern public face the League presented to Thames Street as “large, built of stone, with three arched gates towards the street, the middlemost whereof is far bigger than the others and is seldom opened; the other two bemured [walled] up; the same is now called the old hall.”

The Hansa influence on London’s arrival centre stage in world trade was immeasurable. According to Stow they imported “wheat, rye and other grain” plus “cables, ropes, masts, pitch, tar flax, hemp, linen cloth, wainscots, wax, steel and other profitable merchandises.” Centuries before Vorsprung durch Technik, Hanseatic attention to detail and quality was legendary – from pottery and simple brass thimbles and pins to the pewter for which the City was renowned. German imports were often the ones to own, and Londoners knew it.

The Hanseatic League globalised trade and introduced the towns they occupied to new territories. Distinctive coin-like jettons used by the Hansa for accounts and lead seal hallmarks for wool were unearthed during Museum of London Archaeology excavations at the Steelyard in 1989. The same items are found right across free-trade Europe, from Scandinavia to the south. Yet time and geography would prove the Steelyard’s downfall. Upstream from the growing blockage of London Bridge, the wharf was crucially the wrong side for access to the ocean and the world’s ships.

Of the 24 Legal Quays described in 1559, just three were above the bridge, including the Steelyard. In 1552 during the tumultuous reign of Henry VIII’s son, Edward VI, the Hansa’s economic stranglehold on the City had been broken, encouraged by a challenge from indigenous ‘Merchant Adventurers’. Edward’s half-sister Elizabeth I would go a step further in 1597/8 (when Stow was writing), commanding the Stilliard merchants to quit the city for good – think the Chinese taking back Hong Kong.

The League still owned the premises, which were initially rented to Her Majesty’s Navy for storage. Since 1853, though, virtually every trace of the once mighty Steelyard has been hidden under Cannon Street Station and its railway bridge. The footprint of this economic powerhouse can still be made out and (almost) paced, however.

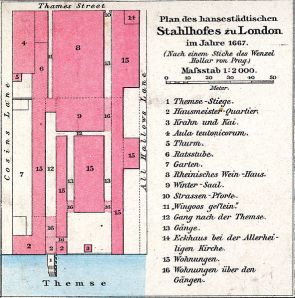

A plan of the Steelyard. It is still possible to walk the ancient perimeters except the Thames. The crane is item no 3.

In Samuel Pepys’ time Dowgate Stairs, one of hundreds of river taxi drop-offs, led from the shore up what is now a skaters’ hangout, Cousins Lane, to Dowgate Hill alongside the Walbrook river.

The diarist was drawn to the Steelyard by its trendy ‘Rhenish winehouse’ (no.8 on the plan) and, from a boat on the river, he watched the Great Fire’s flames lick its walls.

Today The Banker public house offers fine ales and wonderful views over the water where the Steelyard once weighed the world. The next north-south thoroughfare along towards London Bridge, Allhallows Lane, marks what would have been the eastern edge of the Hanseatic presence. The two lanes are connected on the north by Thames Street, just as in the old days.

In 2007 there was a fun Thames Path proposal to link the two lanes on the south via a walkway hanging over the river outside the pub which was grumpily canned on safety grounds. Instead, the pedestrian is diverted under Cannon Street bridge through Steelyard Passage. Here meandering floor lights dimly resemble the course of the Thames, while wall-mounted speakers project clanking and hubbub, suggestive of the old workers and wharves of the middle ages.

In 2007 there was a fun Thames Path proposal to link the two lanes on the south via a walkway hanging over the river outside the pub which was grumpily canned on safety grounds. Instead, the pedestrian is diverted under Cannon Street bridge through Steelyard Passage. Here meandering floor lights dimly resemble the course of the Thames, while wall-mounted speakers project clanking and hubbub, suggestive of the old workers and wharves of the middle ages.

As hard as the City Corporation has tried, Steelyard Passage requires immense imagination to summon that fourteenth century heyday. The modern metropolis’s trains rumble and grind overhead, throwing in the odd curious howl of steel on steel, like a ferrous Hound of the Baskervilles.

From the outside wall of the Banker a long vertical outfall pipe, a few feet in diameter, pokes out roughly where the Steelyard Stairs would have been. Through it spews the famous River Walbrook, once the span of several trading barges, now reduced hurling its fluid into the Thames like some some hungover raver.

The enfeebled Walbrook presents a contrast to the mesmerising power of the tidal Old Father, for which there is no finer vantage point than a window seat in the Banker, as the river shoots round the pillars of Cannon Street Bridge.

The Banker can be found here: http://banker-london.co.uk.

Read about the archaeology of the Steelyard area here: http://www.colat.org.uk/MedievalPort.pdf

Learn more about the Hansa in London here: gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/london-the-forgotten-hanseatic-city