At the end of Jerusalem Passage that tiptoes into Aylesbury Street, adjacent to Clerkenwell Green, there is an easily overlooked green plaque bearing the words: ‘Here stood the house of Thomas Britton (1644-1714) the musical coalman’.

The London Borough of Islington’s words act like a thumbnail to a far richer and more fascinating story. For Britton was no less than the first Londoner to stage a regular musical club night. And the capital’s unique nightlife may have developed in an entirely different way without his influential blueprint.

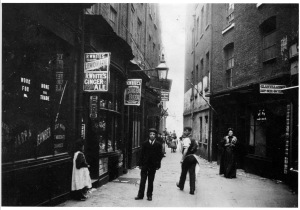

A native of Higham Ferrers, Huntingdonshire, Britton had arrived in London as apprentice to a coal merchant and, like so many rustics before and since, fell in love with the cultural riches offered by the Clerkenwell area, staying to set up on his own account.

At early light each day he was a dust-covered small-coal (charcoal) merchant. But once the sacks were put away he availed himself of antiquarian book and music shops around the neighbourhood and sought out stimulating company.

With his sprightly intellect and fascination for life, science and culture he befriended some of the brightest minds of the day and insinuated his way into higher social echelons at a time of snobbery and exclusion.

Portraits of him – and there were, impressively, several – rarely fail to include a coal bag in the background, as well as his singular library and collection of organs and viols.

It was when he started his regular Thursday evening music sessions that his status as a class-morphing hipster of the late Stuart era was assured.

Neighbour, publican and Clerkenwell chronicler Ned Ward composed the following doggerel for Britton:

Upon Thursday’s Repair

To my Palace, and there

Hobble up Stair by Stair;

But I pray ye take Care

That you break not your Shins by a Stumble,

And without e’er a Souse,

Paid to me or my Spouse,

Sit as still as a Mouse

At the Top of my House,

And there you shall hear how we fumble.

Britton’s club was held in a room ‘very long and narrow’ with ‘a ceiling so low that a tall man could but just stand upright.’ It was just above the filthy rudiments of his coal yard, and reached by a narrow, risky outside staircase. Still, the performers who turned up to play with him included no lesser lights than George Friderik Handel and Dr Pepusch, arranger of Gay’s famous ‘Beggar’s Opera’.

The audience, forking out one penny for a saucer of coffee, was equally stellar. The near-contemporary historian of English music, John Hawkins, inquired about the concerts and relayed what he knew: ‘Britton’s mansion, despicable as it may seem, attracted to it as polite an audience as ever the opera did; and a lady of the first rank in this kingdom, the duchess of Queensbury, now living, one of the most celebrated beauties of her time, may yet remember that in the pleasure which she manifested at hearing Mr Britton’s concert, she seemed to have forgotten the difficulty with which she ascended the steps that led to it.’

Visiting Leeds merchant Ralph Thoresby, in his ‘Diary’ entry for 5 June 1712 related, ‘In our way home called at Mr Britton’s, the noted small-coal man, where we heard a noble concert of music, vocal and instrumental, the best in town, which for many years past he has had weekly for his own entertainment, and of the gentry & c., gratis, to which most foreigners of distinction, for the fancy of it, occasionally went.’

This was a club as cool as any modern Hoxton basement, a must-see for the most discerning tourist, and the hottest ticket in town.

There was yet more to Renaissance man Tom Britton, however. He practised chemistry experiments and had a bewildering array of interests, curiosities and, perhaps, hang-ups – as came to light following his death in 1714.

Britton shuffled off this mortal coil when a practical joke went horribly wrong. A local blacksmith who practiced ventriloquism was induced to throw his voice, pretending to be a supernatural messenger and scaring poor Tom literally to death.

Tom’s widow eventually put his hoard up for sale on 24 January 1715 at St Paul’s Coffee House. The catalogue makes absorbing reading.

Apart from scores indicative of his unusually pluralist music taste, there were several self-diagnosis health books, ‘The Art Of Speaking And Gesture’ and Howell’s ‘Vertue Of Tobacco And Coffee’.

The list also included tomes on physics, chemistry, exploration, bees, Merlin, polygamy, ancient leaders, the gunpowder plot, Judaism, Islam, non-conformism, Rosicrucianism and a tract on ‘The Liberty Of Conscience’.

He owned several volumes by philosopher and ghost hunter Joseph Glanvill, investigations of black magic, ‘A Cat May Look Upon A King’ and a pamphlet, ‘The Hog’s Faced Gentlewoman Called Mistris Tannakin Skinker, Born At Wirkham And Bewitched In Her Mother’s Womb’.

Then comes a surprise: what might represent a c17th rake’s porn stash. Here we find ‘The Secret Mysteries Of Man’s Procreation’, Cleveland’s ‘Rustic Rampant’, the novel ‘The Fair One Stark Naked’, ‘Young Lovers Guide’, ‘Comforts Of Whoring’, ‘Rowland On Farting’ and ‘Petre On Venereal Disease’. Oh and, perhaps understandably, a guide to divorce law.

Among the hundreds of books in this fantastically revealing collection, lovingly compiled by one of London’s great cultural pioneers, there was just one book on coal. And that, my friends, is a proper Londoner’s work/life balance.