A little known passenger in the chaotic British withdrawal from Palestine in 1947 was Lady Hilda Petrie. She was 80 and had hoped to see out her days in Jerusalem, the city she had resided in and loved for decades.

Her husband, Sir Flinders Petrie, had predeceased her five years earlier and he was buried on Mount Scopus. Well, most of him. He had actually bequeathed what he considered his priceless asset to science, for reasons we will soon discover.

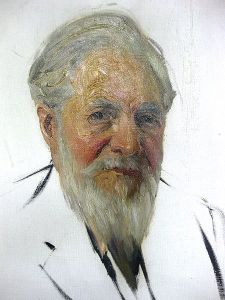

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie was a world-renowned Egyptologist and father of modern archaeology. He excavated more than sixty of the most important sites in Palestine and Egypt. Equally as important as his amazing discoveries in, say, the Valley of the Kings (he employed Howard Carter, who was later to discover the tomb of Tutankhamen) were the pioneering archaeological methodologies he devised that are still in use to this day.

He was one of the first to recognise the importance of context and the value of data-gathering, and evangelised a more gentle, painstaking approach to the actual digging itself. His principle breakthrough, though, was to work out a chronology by which to date his discoveries.

But those are not the only fascinations surrounding this revered Victorian scientist.

Petrie, one of archaeology’s icons, was also a vehement proponent of eugenics: the belief that racial pools can be improved by selective breeding. He enjoyed a close working relationship with key eugenics proponents Francis Galton and Karl Pearson.

Over the course of fifty years in trenches Petrie regularly sent skulls and bones back to Pearson at his Anthropometric Laboratory at University College London.

The Eugenics Laboratory at UCL relied heavily of data from Petrie’s finds to support its tehories. Galton also hired Petrie to photograph idols and statues for his book ‘Racial Photographs of the Egyptian Monuments’ (1887).

That book was the key publication of the nascent eugenics movement, in later years providing a historical gravitas for new exponents to exploit. All three men proposed ‘selective breeding’ to maintain the quality of the British race.

Eugenics was discredited as naive racism at the start of the 20th century, but returned to wreak havoc and destruction under its greatest advocates, the Nazis.

It is unclear how far our present view of ancient history has been clouded by the legacy of Petrie’s racialised doctrine. (And, indeed, the archaeologist held what might be described as enlightened views about Arab/Jewish cohabitation in what was to become Israel.)

Yet the pseudo-science of eugenics had a clear and inadvertent impact on Petrie himself.

On his deathbed the revered archaeologist donated his head and brain to the Royal Society of Surgeons, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London, so that it might be studied for ‘further exploration of the British genius.’

Unfortunately, he died in 1942 in war-torn Palestine, and while his torso was buried in the local Protestant Cemetery, the rest of him was stuck in limbo because of the conflict.

According to archaeologist and historian Neil A Silberman, Petrie’s head had been ‘surgically removed by the Jerusalem hospital director, placed in a jar, and preserved with formaldehyde’ when he died. But it had to be stored at the American School of Oriental Research until repatriation to Blighty could be arranged.

While at the school, Silberman was informed, students were wont to use his head as a ‘prop for grotesque practical jokes and a source of horrified reactions.’ (Similar stories surrounded the head of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who died in 1832, and bequeathed his body for public display at University College London.)

Another version tells it that Lady Hilda, who lived at the American School, kept her beloved husband’s head under the bed.

Eventually, in 1944 the head was shipped to London by the Palestine Department of Antiquities – labelled as an antiquity. Some of the process can be tracked in correspondence in the Royal College archive.

However, when the famous bonce was finally viewed at the Royal College, some who knew Petrie allegedly noted little resemblance in age or hair to the famously white-bearded Egyptologist: the beard in the jar is black.

Petrie’s head still languishes there today, viewable by appointment, with the Royal College staff perpetuating the mystery by remaining non-committal about whether this is the real head of Flinders Petrie, or – god forbid – that of someone racially inferior.

It is quite ironic that Petrie’s head, filled with hopes of eugenics research, may have gone awol just as Hitler’s disastrous genetic doctrine was collapsing.

I love the post. However your use of “predeceased” is ungrammatical. The word “predeceased” is used to mean “died before the subject died.” The word you are looking for is “died.”

Have you seen Shimon Gibson’s photo which he claims to be of Petrie’s head?: http://jamestabor.com/2012/08/01/remembering-sir-flinders-petrie/

…Petrie seems to have dyed his hair black from pure white! Also, Gibson has access to the Royal College of Surgeons’ private collection (where The Man Who Discovered Egypt BBC4 doc claims it resides) does he? He seems a bit of a quack.

Thanks, I will check it out. Rick